Tantalus was a rotten apple! An invited guest on Mt Olympus, he stole nectar and ambrosia and brought it back to impress his friends. But that wasn’t the worst. Later when the gods came to dine with him, he cut up his own son, Pelops, boiled him, and served him to his guests. The gods suspected something was off with the menu and declined to partake; but poor Demeter, distracted by the loss of her daughter, Persephone, took a bit of shoulder.

Zeus ordered that the parts of Pelops be collected and that he be put back together. Hephaestus made him an ivory shoulder, and he grew into a handsome youth, married, and had children of his own. Zeus killed Tantalus and then punished him further by making him stand waist-deep in water while overhead he was shaded by a large apple tree ripe with fruit. However, whenever Tantalus went to drink the water, it dried up; and each time he tried to pluck an apple, the wind blew the branch out of reach. He was trapped inside perpetual desire.

Orchardists desire a beautiful, abundant crop. They worry about the crop all year long. There’s no off-season. Weather can freeze the buds or the blossoms. Even the almost ripe fruit can be the unlucky destination for thirty seconds of hail. Then the apples will be pock-marked and susceptible to disease. Yet, still, growers of apples persevere. There’s something about growing fruit that challenges the soul. And the best part is that it requires hands-on attention.

How surprised I was to learn of a robotized apple picker being developed by Abundant Robotics, Inc. The picker will be drawn by a tractor with nozzles reaching out, up, and down, vacuuming the fruit off the tree. Each step of progress seems to take humans away from touching what we do, touching what we grow, automatizing our lives. Touch is a profound human experience. Think of an infant and how these two senses, touch and taste, are the foundation of her first relationships.

When I first saw the advertisement for this small farm in Harvard, MA, it said five bedrooms, a detached garage/barn, apple orchard, and a chicken coop. At that moment in my life, I was unsure about everything. I had never before contemplated owning a house, but I had to find a place to live. I wanted a place that would have rooms for my three children and a studio for making sculpture. I walked with a realtor through the kitchen where dark pine boards covered the walls and ceiling. There were no drawers or cabinets, only open shelves for plates, bowls, and glasses. Above a wood-burning cook stove hung a patchwork of blackened iron pans. This was a real work kitchen. We walked upstairs and I thought, If the house has hot water, everything will be fine. In the master bath, I turned on the hot water faucet in the 1960s avocado-colored sink. Warmth ran over my fingertips.

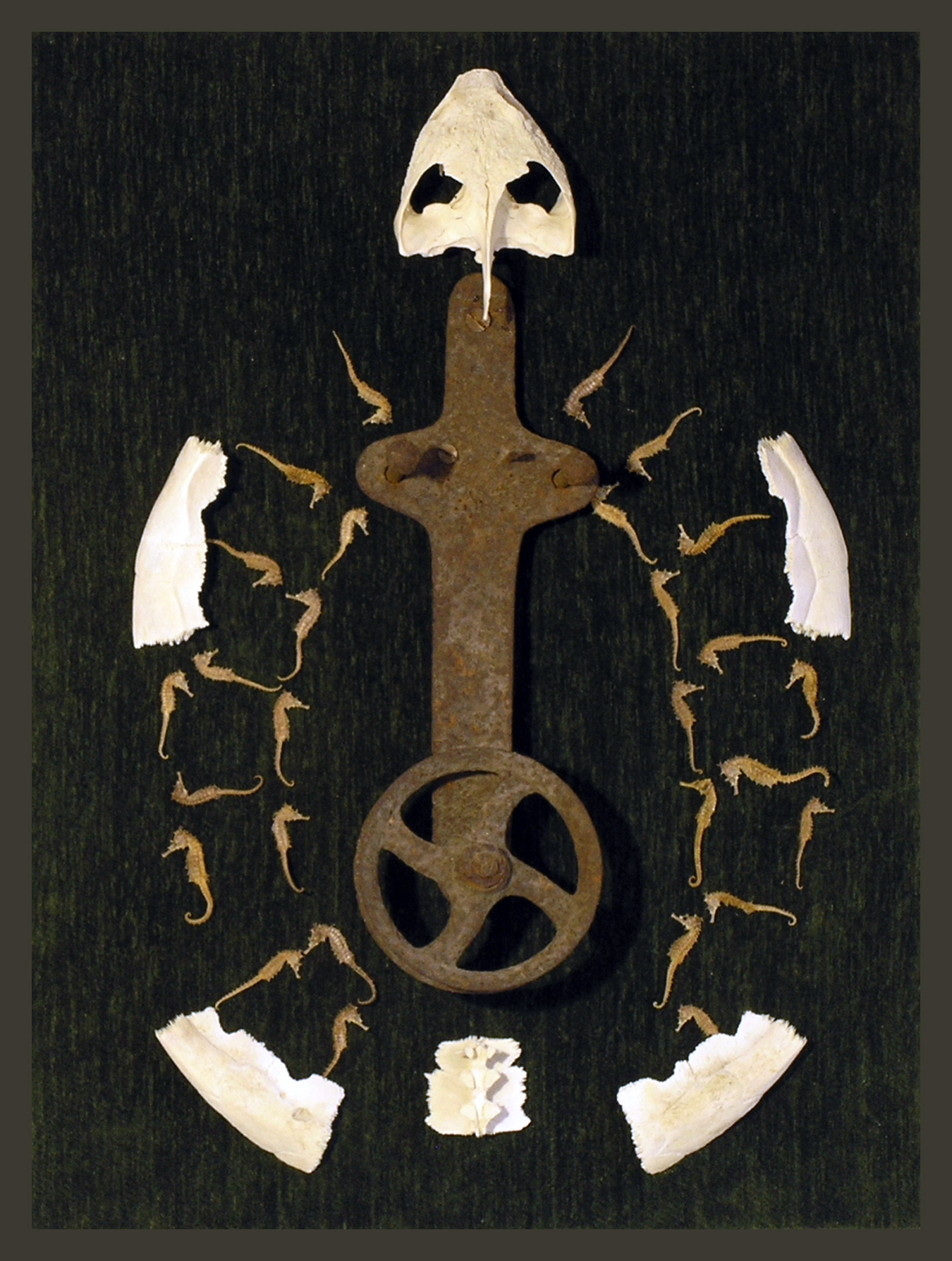

Maybe because I am a sculptor I trust what I feel with my hands. That touch of warmth gave me the confidence to move to the farm. But I had no idea that once I started to grow apples, I would become like Tantalus, desirous of plucking more and more fruit.

Women and Apples, Photo Credit: Carol J. Hicks

Even with extreme shifts of weather and unexpected environmental conditions, I persist. In winter, walking through the orchard, bending down the branches, pruning off what is no longer needed, and running my fingers over the frozen fruit buds, I fall again in love with the promise of fruit. And after a full day pruning in the winter cold, I sit in my favorite armchair and read the descriptions of heirloom and modern apples in my stack of saved nursery catalogues. I can’t help but be tantalized. I order a few new varieties for spring planting — a perfect Valentine's Day gift!