In 1887, the United States Department of Agriculture in Washington, D.C. hired an immigrant artist to be on its staff. Born in Germany, Wilhem Heinrich Prestele’s parents emigrated to the United States with their family in 1843 when Wilhelm was five years old. His father, Joseph Presetele, had been a head gardener for King Ludwig I of Bavaria and a painter of fruits and flowers.

In his mid-twenties, William Henry Prestele, as he was now called, was a struggling artist living on Ninth Avenue in New York City with a wife and three children to support. William had inherited his father’s abilities, and when the opportunity to make a series of nurseryman’s plates for a Bloomington, Indiana, nursery came up, he packed up his young family, moved from New York to Indiana, and started his career as a botanical illustrator. None of the plates from this time exist, but an 1869 edition of Gardener's Monthly wrote:

We have now before us a fruit piece...prepared by W. H. Prestele. We are in the habit of admiring European art in this line, and have often wished Americans could successfully compete with it. We now have it here. We never saw anything of the kind better executed from any part of the world.

Prestele’s next position was in the USDA’s new pomological division. He painted watercolors for the National Agricultural Library’s collection, which grew to hold 7,584 watercolors of different varieties of fruits and nuts, including 3,802 paintings of apples. There were 21 artists who contributed to the collection, and nine of them were women.

Dolls Autumn Apple painted by William Henry Prestele, U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, Maryland

The watercolors and drawings of fruit by these artists are among the most beautiful of early American art, no less amazing than the landscape paintings of the same era by the likes of Thomas Cole and his student Frederic Church. Though these artists had widely divergent subjects—towering mountains and flowing water on the one hand, versus seedpods, blossoms, and fruit on the other — they shared a desire for scientific accuracy and transcendent awe for their subjects. Americans’ appreciation for wilderness seemed to have paralleled their enjoyment of the apple.

The consumer knew that some apples were better for dessert, and some for pies, while others needed to be stored for several months to develop their flavors. The public appreciated the details of their differences — one licorice, another bitter, some with hints of orange, others lemony, nutty, or cinnamon-ny. The Nomenclature of the Apple by W. H. Ragan, printed in 1905, listed the unique apples offered by nursery catalogues from 1804 to 1904 — there were 6,654! The 19th century was a heyday for apples.

In the 1920s and 30s, with more people living in cities, the industrialization of food production advanced. Longer shelf life and ease of shipping became more important than taste. It was far easier to focus on a few varieties for mass production. It was all about commerce, all about looks; and the appreciation of the unique tastes of locally picked apples vanished. By the time my mother shopped for apples in Philadelphia in the 1950s and 60s, there were only a handful of apple varieties available in the supermarket. I remember liking the tart Winesap, while my brother preferred the sweeter Red Delicious.

I love the fact that the USDA hired artists to create extravagantly detailed renderings of fruits and nuts. We have lost a quality that comes with hand-painting, handwriting, and drawing. Sharing is a button on Facebook, and a catalogue is a collection of photographs. But more importantly, as these few varieties were crossed and re-crossed, their good taste and their health diminished. Red Delicious stayed a lovely red on the outside, but inside became mealy and boring. Unlike in a diverse orchard, where one variety might suffer insect pressure, while other varieties are ignored by pests; the insects prepared thorough, full-on attacks and feasted in these monocultures. As a result, pesticide use greatly increased. As any biological grower knows, diversity is key for healthy agriculture.

Diversity is also key to responding to climate change. A Northern apple grower might soon need to plant some Southern apples that don't require as many chill hours. Apple trees start to grow only after they receive a certain number of chill hours followed by heat. Each variety has its own ‘chill’ requirement. To read more about chill requirements for both apples and people read The New Year 2016 blog.

Diversity is key in every aspect our lives — the food we eat, the people we interact with, the news we read. We don’t always realize how we insulate ourselves and build walls around many aspects of our lives. We need healthy ecosystems just as much as we need healthy societal systems. And we need imagination! My friend, Vico Fabris, paints beautiful imaginary botanicals.

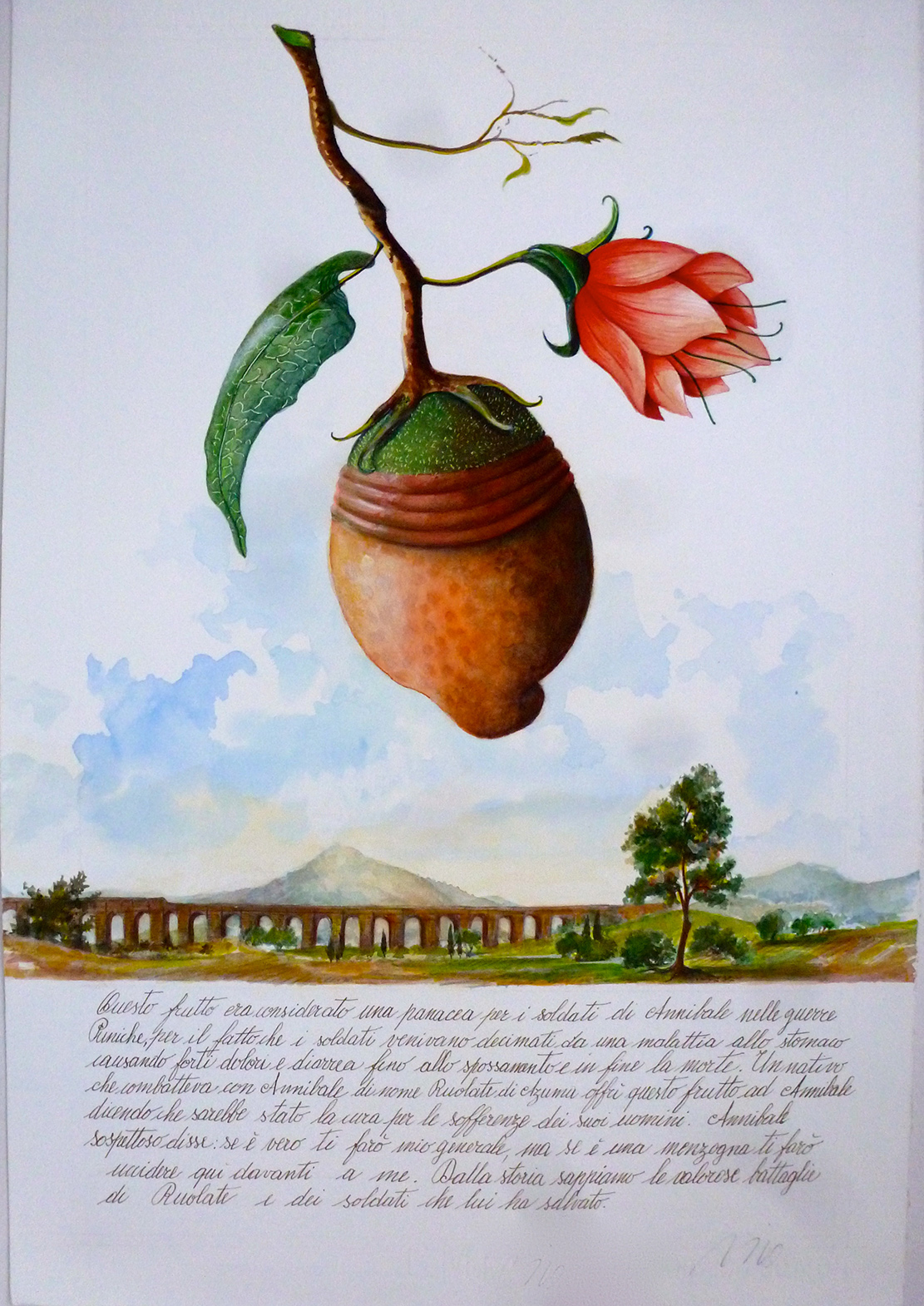

Azumacea, Vico Fabbris

Written in Vico’s native Italian under this painting is local legend about the plant, its medicinal properties, fragrance, and source. Vico celebrates diversity in every one of his paintings.

I doubt either of us could find support as artists in this United States government. When our President Elect asked Warhol to do a portrait of Trump Tower, Trump was “very upset that [the series] wasn’t color-coordinated,” and the deal fell through. We’ll all just have to take down that wall brick by brick., and keep America as artistically, botanically, and socially diverse as possible.