I’ve been reading the book, Sapiens, by Yuval Noah Harari. The author’s broad lens, an overview of our species from early man to the present time, is helpful as my focus has been so closely fixed on the daily headlines. Our brothers and sisters, members of our same genus, Homo, like Neanderthal man, Homo erectus, Homo soloensis, Homo floresiensis, among others, lived on this planet for millions of years. Then, Homo sapiens (Wise Man so we defined ourselves) evolved in West Africa, and spread throughout the Asian landmass, and all of the other members of our genus disappeared. Theories abound and no one really knows whether we were responsible. However, we do know a little about early sapien ways.

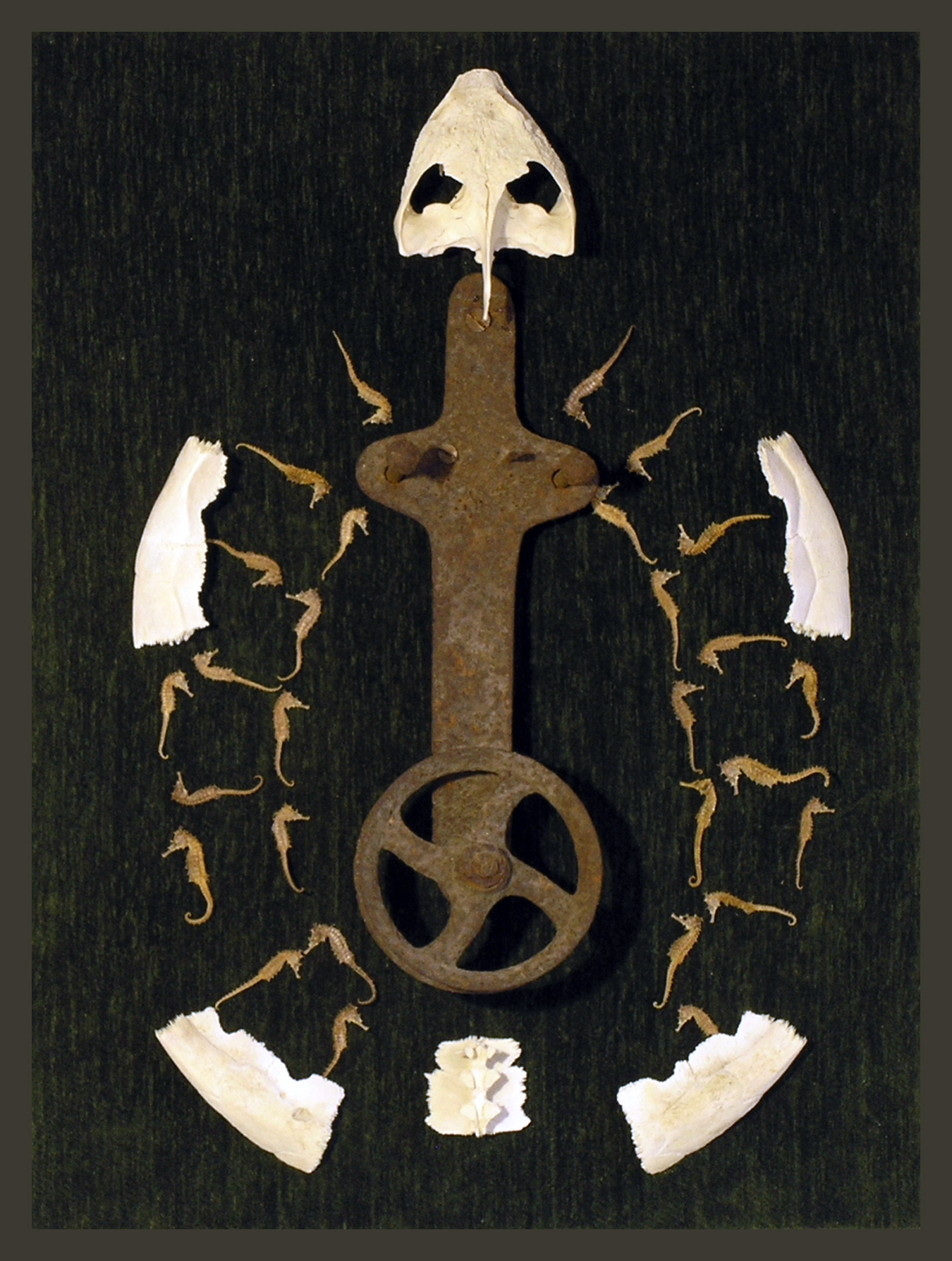

Ancient Turtle, Sculpture, LH

Homo sapiens, not content to stay in any one place, forged ahead. The first place we colonized was Australia, quite an undertaking considering the distance over land and water, but Homo sapiens did what we had been evolving to do. We stepped onto the landmass of what we call Australia where there were no other human beings, and changed it forever. Sapiens encountered great animals like 450 pound kangaroos, giant koala bears, and dragon size lizards. However, within a few short millennia, twenty-three of the twenty-four mammals weighing over one hundred pounds went extinct. Large animals have only one or two offspring and the gestation period is long. If the animal’s young are killed, even as few as one every month or so, in a few thousand years, they die out. As hunter and gatherers, we were not necessarily aware of the changes we were causing, but science points to the irreversible transformations we triggered.

Homo sapiens evolved extremely quickly. Unlike Homo erectus, for example, who used stone tools and remained essentially the same for two million years — Homo sapiens wielded the hoe, the pen, and the brush, becoming farmers, and then, artists, politicians, scholars, scientists, and philosophers in a relatively short time. We developed a sophisticated language. Language, the big differential between us and other species, is how we shape our world. With language we decide collectively what to believe in, and how we envision the future. Harari makes the case that so much of our culture is myth anyway — it’s what we collectively believe. Sapiens became powerful because we learned how to collectively believe in myths—the myth of our economic system, the myth that there are countries with borders, the myths of religion. There is no scientific basis for any of these. From an historical perspective, you could say that religions developed and became dominant in a particular area for no more reason than a particular butterfly has blue wings. Perhaps we need to start dismantling some of our myths — especially the ones that separate instead of seek our commonality.

The assumption is that we have evolved from our wild and wooly ways, and developed and believe in sophisticated ideologies that we hold to be true and enable us to live peacefully and cooperatively with each other. But we don’t live peacefully or cooperatively with other sapiens or other creatures on the planet and we haven’t for many years. It’s almost as if our shadow side is finally coming forth and demanding to be seen and heard. It’s not this one election — nothing arises without a cause. On our planet millions of acres of forests are gone, our topsoil is disappearing at alarming rates, our biodiversity is shriveling, and climate change is going to make large areas inhabitable because of high water and high temperatures. Greed, intolerance, and ignorance have all played their role.

This week I’ve been pruning the apple orchard with Denis Wagner who first taught me to prune the trees over a decade ago. We prune in silence until one of us asks about a certain branch. Sometimes we both stand back and gaze up into the crown of the tree wondering if there are some branches that need to be pruned out to encourage growth. We confer amiably and respectfully. We both know that there are multiple choices, and no one knows exactly what is best, but each cut changes the course of the growth of the tree. In the orchard it’s easy; we both want the best for the tree.

Does this analogy translate to the world? Not easily. Denis and I usually agree, and it takes very little for either of us to back down and harmonize with the other. But it does make me think that we need to talk, we need to stop building walls, stop filibustering, and stop being right. History has proved that unless we live compassionately and empathetically, we all suffer.

Apple Pressing, LH, 2016, Collection: Madeleine Lord

Hunters and gatherers related to their world with an early form of religion, what today we call animism. Animists believe that humans and animals can communicate — that we can and do have relationships not only with animals, but with trees, and even rocks. We share the world with these other creatures, both animate and inanimate. As we developed, we seemed to have forgotten that relationships are important. We have been focused on the power and the rights of the individual. Perhaps it’s time to throw out this notion of the sacrosanct individual, the one who signs executive orders at 4:42 pm on a Friday afternoon and changes the lives of thousands of people. But that means each of us, too, must loosen our own hold on our individual identity and join the fray – the messiness of living with all of our brothers and sisters, animate and inanimate, no matter what they do or do not believe in.

Above all, we must enter the dialogue, speak up, loudly, and compassionately. We need to tell new stories that inspire and shed light on our earth, our home, our commonness. We are all Homo sapiens. We all have a beating heart.

Family Photo: My son, Alex, and his Dada, 1988