Last week we had a grafting workshop at the farm. Grafting is an old art form but it can also happen naturally. When two different trees grow close enough together so that their branches touch, eventually the bark will rub off, and their cambium layers will join. They will begin to feed each other and can also share traits. For example, if I wanted to grow a pinyon pine in New England where the climate is too cold for the pinyon root, I could plant a white pine and a pinyon pine side by side. Once they were both growing, I would bend their branches so they crossed over, and encourage their union by shaving some of the bark off of each branch where they touched. After they became joined like Siamese twins, I would cut off the roots of the pinyon pine, and saw off the top of the white pine. My new tree would have white pine roots, which are well adapted to our climate feeding the pinyon pine. I could then harvest delicious pine nuts in New England (unless the squirrels got to them first).

When I moved to the farm I didn’t understand the meaning of the word graft, nor did I know that all apple trees were grafted trees. Our workshop introduced the participants to the two most common types of grafts used on apple trees — the bark graft used to change the variety of an existing tree, and the whip and tongue graft used to graft onto one-year-old rootstock. Each person went home with one or two young apple trees chosen from the twenty-five varieties I had on hand for them to graft. (We’ll be offering this workshop again!)

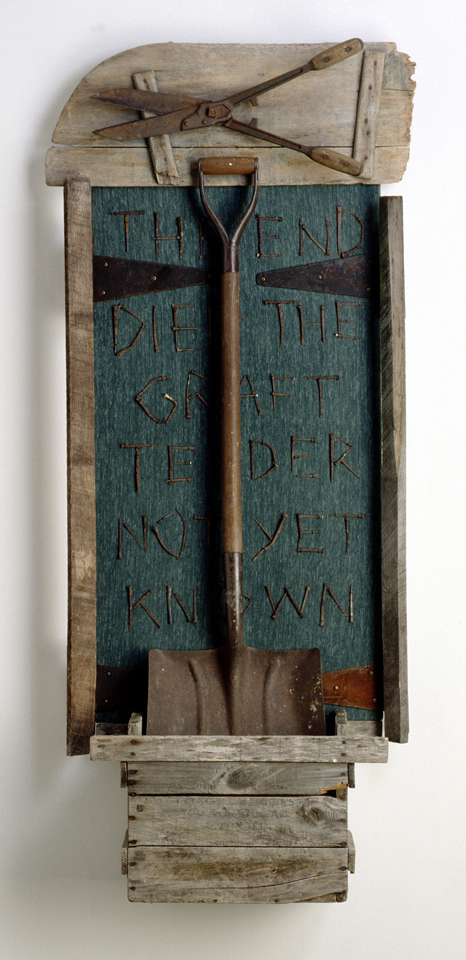

What I didn’t tell the people taking the workshop was that during the first year after my move to the farm, I made a sculpture titled, The Graft. It was a challenging time. My marriage of twenty years had ended and I didn’t know the first thing about being an orchardist. The orchard of abandoned trees felt like a dying landscape. Almost a hundred of the three hundred trees were dead and needed to be removed. I wrote this poem on the sculpture using rusty nails to form the letters: “The end died — the graft tender — not yet known.”

The Graft by Linda Hoffman

I didn’t really know what the word graft meant, but I must have unconsciously known that it was related to apples and that it expressed something that was tenuous. For when we graft, we never know if the graft will take. The young trees I grafted last week are sitting on the porch away from direct sun, and I check them daily to see if they have begun to push out new leaves above the graft union. That’s the sign of accomplishment — a few tender green leaves.

Grafted Apple Rootstocks

As far as the sculpture goes, I still feel tenderly about it. As far as my life, I feel like I can say that, after fifteen years, the graft took. Indeed, it has been an amazing journey of loss and rebirth. As for these new trees, I will let you know how they do in a future post.

Postscript: When I looked for a photograph of The Graft in folders of sculpture from the early years on the farm I couldn’t find it. I was all set to take a new one, when with my daughter's help, we found it in the folder of photographs of my sculpture from 1999 — two years before I moved to the farm. How could that be? I wondered. We checked the meta-data on the image and it was indeed 1999. I decided to leave this post as written demonstrating the prophetic connection between my art and life. It certainly suggests that art can enable us to bypass the rational mind and reveal a hidden truth.