The canvas tote bag says, “East Fork is a vessel.” But I know East Fork is the little itty bitty stream that moves through the property at the end of Ras Grooms Road, in Marshall, North Carolina. I remember sitting with my oldest son, Alex, on the concrete stoop of a rundown house at the end of rural road, far from anything, a barren bit of land where the sun doesn’t crest the ridge until 11 am. A simple shed, an old tobacco barn, a field plowed by a neighbor, and a mailbox on a crooked post occupied the flatland; the rest of the 40 some acres were steep and covered with gnarly dense rhododendrons and forest trees. Alex was feeling, “What have I done?” I was feeling the same, but didn’t dare say. It was a shocking beginning; the kind that forms a knot in your chest that can take a long time to unravel.

Alex had spent three years as an apprentice with two North Carolina potters, Matt Jones in Big Sandy Mush outside Asheville, and Matt’s teacher, Mark Hewitt in Pittsboro. Then it was time for him to go out on his own. Alex found this little ‘holler’ where the East Fork stream flows and, pressured by a real estate agent who assured him there would never be anything else available for a price he could manage, bought it.

I was visiting with Alex the day after he had signed papers. I would soon leave him alone in his little, dark house. It would take time and effort to set up a rudimentary pottery so he could begin making his own pots. Two men from down the street appeared, carrying a couple of six packs of beer. I feared that they would arrive daily to drink with him. I felt the fragility of my first born son at that moment; still young, not yet a man — finding out how to become one. I reflected that in some way he was doing what I had done when I left our family home, moved to a farm with an abandoned apple orchard, and began a new life. I knew personally the feeling of isolation and fear that comes after plunging into the unknown. But I was older and had more support. The changes at Old Frog Pond Farm took many years. I was worried for him.

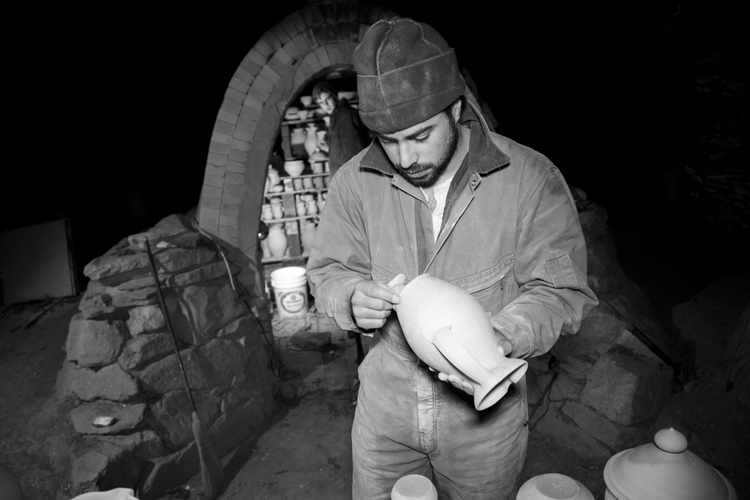

Alex built a beautiful wood fire kiln on the site, and then set about making pots. Friends and family helped. It felt like a slow beginning, but two years after we sat on that cracked cement stoop together, East Fork Pottery was born, and hosted its first kiln sale.

Alex in the Kiln, Photo: Nick Matisse (his brother)

Early on, Alex met a beauty from Los Angeles. What exactly she was doing on a goat farm nearby is hard to know. Connie’s prominent LA lawyer mother visited — trying to understand why her Berkeley grad was now milking goats, and hoping she could delicately move Connie into the next part of her life. Connie and her mom were at the Asheville Farmers Market, when looking around for a friend for her daughter who didn’t say, “Maaa, Maaa,” Connie’s mother pointed to Alex and said: “See that boy, he looks nice. You should go talk with him.” Eight years later, Connie and Alex have two beautiful babies, Vita and Lucia, and Connie is artistic director of East Fork.

Connie and Alex in the Kiln. Photo: Nick Matisse

Alex could have followed in his mentors’ footsteps, opening Alex Matisse Pottery, but, instead, he wanted community. East Fork is a team of great potters, kiln firers, salespeople – and they're all under forty. This youthful group is creating a successful company that makes beauty and brings it to the world. Tall, thin John Viegland, another traditionally trained North Carolina potter, joined Alex early on. He is the financial manager and works at the pottery full time.

John Vigeland in the Pottery

One of their first hires was Amanda Hollomon-Cook. She is now production manager and potter, organizing all the numbers of plates, bowls, and mugs needed, and in what glazes. When she goes home, she works in her own studio on ceramic sculpture. Connie recently did a photo shoot with Amanda and her sculpture — a beautiful collaboration!

Sculpture Amanda Hollomon-Cook Photo: Connie Coady Matisse

I am proud to be Alex’s mother, and Connie's mother-in-law — and I still worry! But take a look at their website – their pottery, the other artisans’ work they promote, and the journal that Connie writes. You will want to be part of this back to the earth and into the marketplace movement! Clay dug from the hills of North Carolina, old world craftsmanship, skill, liberal politics in a not-so-liberal state. “Down with the patriarchy,” says two-year-old Vita. The only difficult family issue is that Connie is a Dodgers fan, and Blase, my husband, is ardently national league, he grew up in Malden outside of Boston. Otherwise, we all eat off plates stamped East Fork.

***While Blase and I are traveling to Florence and Venice for ten days, there will be a two-week pause in the blog.