To peel a boiled potato is a rare treat. —François Ponge

Pomme de terre in French means apple of the earth. Like apples, les pommes de terre have been on the planet for thousands of years and have been cultivated on all every continent except Antarctica. They sprout easily from the tuber itself: a rarity among plants, unlike a seed that is often surrounded by fleshy material or a hard pit.

A forgotten bag of potatoes!

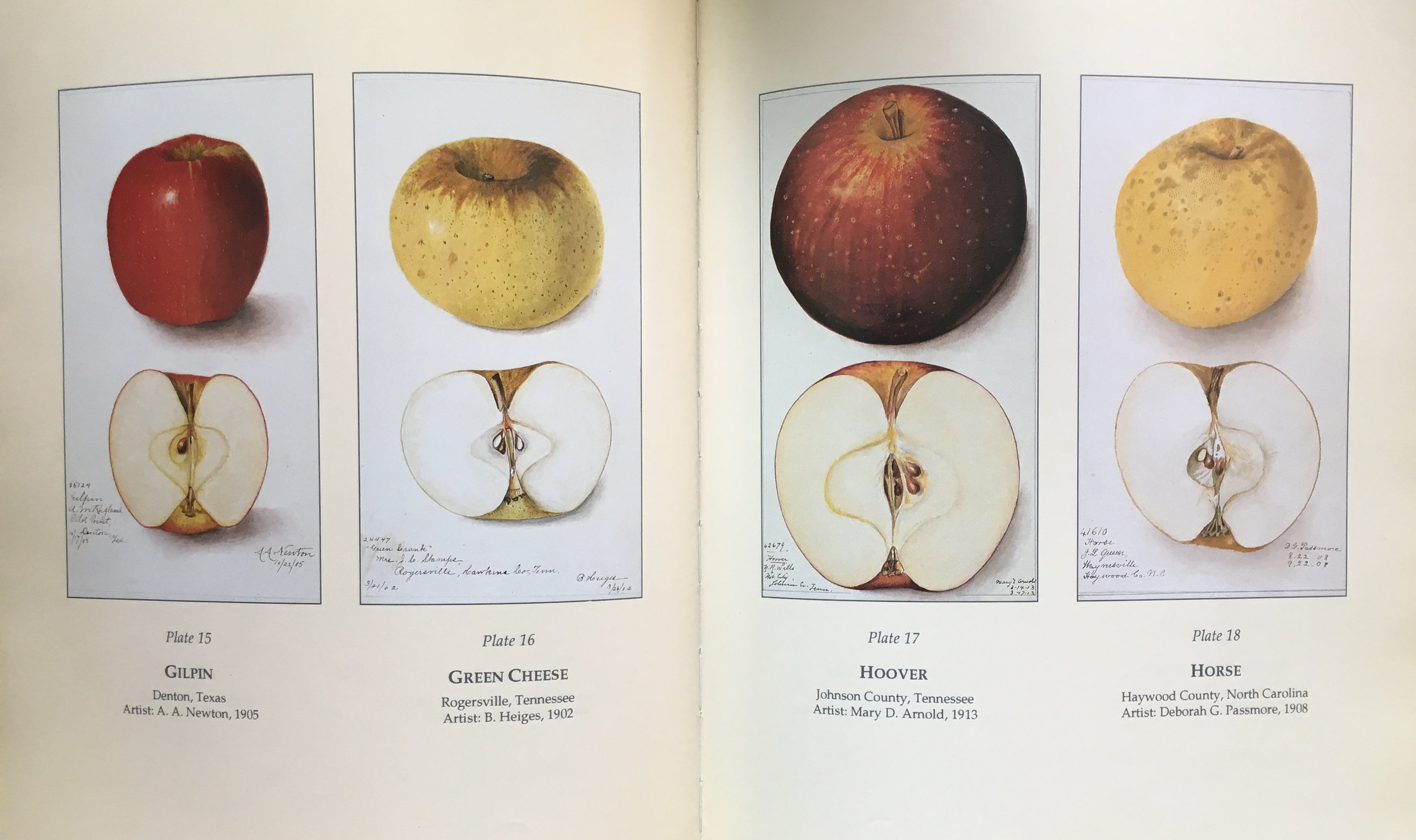

The potato had its start in the soil of South America between 8000 and 5000 BCE. Today in the Andes about four hundred varieties of potatoes are grown. A single farmer in Peru might plant thirty to fifty different potatoes. Some of these potatoes she knows are resistant to drought or disease, others keep longer once they are dug, some crop early, some late. Peruvian potatoes, like heirloom apples, have many-shapes: round, oblong, conical, to name only a few, with hues of red, brown, yellow, purple, and blue that are marbled, speckled, streaked, striped, and mottled. Twenty-five or so varieties are sold in supermarkets and it seems that Peruvian shoppers are familiar with each potato’s unique characteristic.

Near Cuzco, Peru, six thousand families live in the world's first "Potato Park." Here residents and scientists test the tolerance of different potatoes to changing temperatures in a 22,700 acre living laboratory. Climate change has affected potato growing in Peru as it has crops across the globe. Potatoes that grew at 3000 feet now must be grown closer to 4000 feet because of the rise in average temperatures at these altitudes. And in low altitudes, it is now too warm to plant them. I am worried about our unseasonably warm local temperatures taking our fruit trees out of dormancy too early.

In his book, Potato: a history of the propitious esculent, John Reader writes that Juan, a Peruvian potato grower, told him that it had been a bad year for potatoes because an early frost had harmed the young plants. But his crop did all right. He had some plants that were frost tolerant, “and also tall enough to lean over and protect their weaker brothers.”

Farmers learn from their plants; being a farmer is being a nurturer. Humans need to eat, and if we are going to eat, we need to be kind to our crops. Today, so many people exchange money for food that we have moved far away from the mentality of being a nurturer towards plants. Money doesn’t grow on trees, and we don’t have to cultivate money with any sort of empathy. Is it any wonder that we have President Trump in the White House? His product, wealth, requires little compassion to grow, only aggressive boasting to propagate the Trump brand.

There is pressure on the Andean farmers to sell their land for profit. But it is organizations like the International Potato Center partnering with the “Potato Park” to support the Andean farmers so that their native knowledge will not be lost. Trialing the adaptive properties of hundreds of potatoes will hopefully insure that their children will eat food grown in the Andean soil, food will sustain them and their culture, as it has for millennia.

The French poet, Francis Ponge, wrote prose poems about single objects like the potato. Let’s not forget in these days of too much bad news to marvel at the simple potato.

La Pomme de Terre

To peel a boiled potato is a rare treat.

Between the cushion and the thumb and the point of the knife held by the other fingers, one seizes — after piercing— one of those lips of rough, thin parchment and pulls it towards one to detach it from the appetizing flesh of the tuber. […]

—François Ponge, in Selected Poems, edited and translated by Margaret Guiton

There are some potatoes with such papery thin skin that there is no need to peel away the parchment. And some are too beautiful to eat.

Freshly Dug Love!