The painter Paul Cézanne once said, I will astonish Paris with an apple! He painted the apple over and over — more than 250 still life paintings with apples. Some feel dark and foreboding while others are raucously joyful; but Cézanne wasn’t interested in depicting emotions, he painted light. He painted light that created shape. With small brushstrokes of color, he crafted the landscape he loved near Aix-en-Provence, the nestled houses, Mont Sainte-Victoire, rocks and trees; and back in the studio, his many magnificent still life paintings and portraits.

In the history of art, Cézanne is the beginning of modern painting. He didn’t paint like the Impressionists, with their luminous pictures of an ephemeral moment, but created solidity, the absoluteness of shape — or presence — the reality of an object as it embodies itself.

I was telling my friend, Jody Hojin Kimmel, a Buddhist priest and artist, that I was hoping to write a blog about apples and Cézanne. She told me about a little book, World View of Paul Cézanne: Psychic Interpretation, by Jane Roberts. Roberts wrote that she channeled the book from Cézanne. I found it on Amazon and looked for references to apples. (I also ordered a copy.)

The apple’s color doesn’t stay in the apple, for if you observe carefully, you will notice that the colors bleed outward, escaping the apple’s shape; and that the colors of nearby objects are also contained, however minutely, in the apple . . .

Roberts (or Cézanne) is saying that the apple is not an isolated object, but part of its surroundings. Taking this idea further suggests that the lines we give to objects are not hard and fast boundaries. And extending the idea to ourselves, to our own bodies, means we are not distinct entities. I think Cézanne would agree that there is a continuum between object and ground, between subject and object, between tree, rock, and sky. One of the important realizations of the Buddha was that we are all connected, interdependent, not separate. You might say that Cézanne’s paintings of apples were explorations into the very nature of the spiritual life.

In another reference to Cézanne’s apples, Roberts wrote,

Apples seem to have their own colors made of many combinations, and almost just above these, other colors stain the original ones. And these top colors carry more of light’s shifting characteristics, for they will seem to float above the apple in uneven layers, with peaks and valleys-‑like a colorful sea of surrounding objects, through which we peer to see the objects underneath.

Roberts is describing how Cézanne painted the layers of his perceptions, as he built up the painting of an apple with transparent colors. It’s as if the skin of the apple was multi-dimensional, kaleidoscopic.

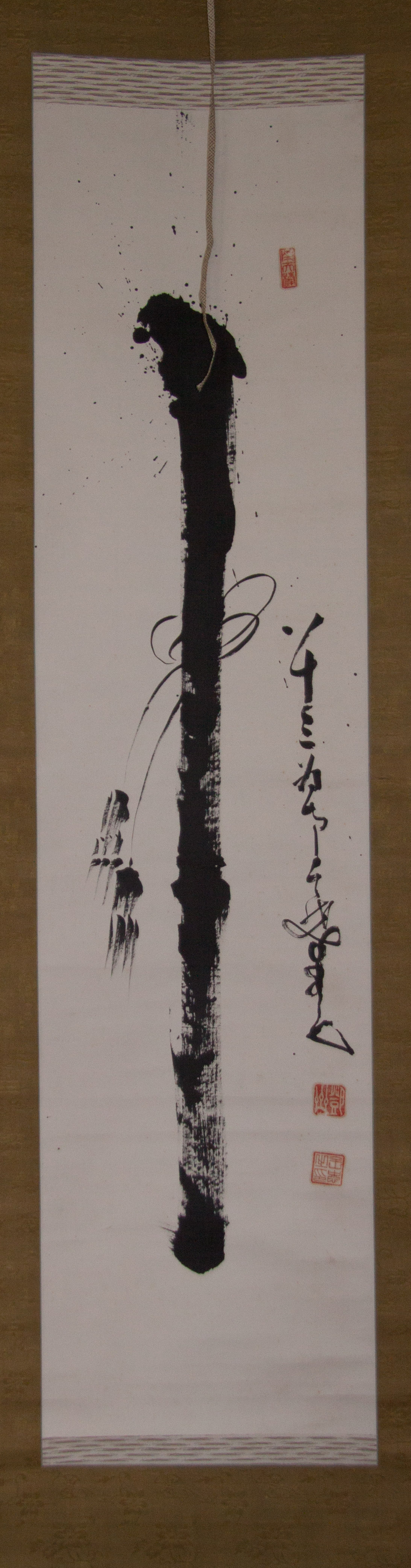

Cézanne was completely attentive to his subject. His paintings don’t express any commentary or subtext. The apples are apples; the rocks are rocks — and the painter disappears. When people say, Oh, I can’t paint, they are talking about creating a likeness. If they really want to paint, they must become their subject completely, and the result will be art. It might not be a likeness, and it might not be great art — that takes great skill, patience, and a lifetime of dedicated practice every day. But no matter, others will sense the truth in their work, the truth of the artist’s experience. That’s why I find abstract art can be so powerful; there is a profound merging, beyond meaning, where subject and object cannot be differentiated subject.

This fall we will have an Apple Painting workshop at the farm. We’ll look at some photographs of Cézanne’s paintings and then choose apples from the orchard to arrange and paint. Let me know if you’d like to be on the list to receive information. Cézanne said, Painting from nature is not copying the object . . . it is realizing one’s sensations. We can all do that.