A large silver coyote approached me in a clearing in the woods where I stood. She seemed hungry and threatening and I was terrified. So terrified that I couldn't find my voice to shout or wildly wave my arms to scare her away. I turned to run and then saw that coyotes were coming out of the woods and approaching from all directions. They would surely tear my body apart and feast on my bloodied limbs.

I considered this picture, then paused for a moment. Something in me changed. “No!” I screamed and I began madly gesticulating The coyotes were silenced as if struck mute, and they turned back in the direction from where they had come. I woke up with a good feeling — something I use as a barometer for my dreaming. Inside the fear, I was paralyzed, but when I found my ground and let go of my fear, I could act effectively. This change happened in a split second. There was no lengthy dialogue, but there was a listening, a facing the reality of the situation without projections.

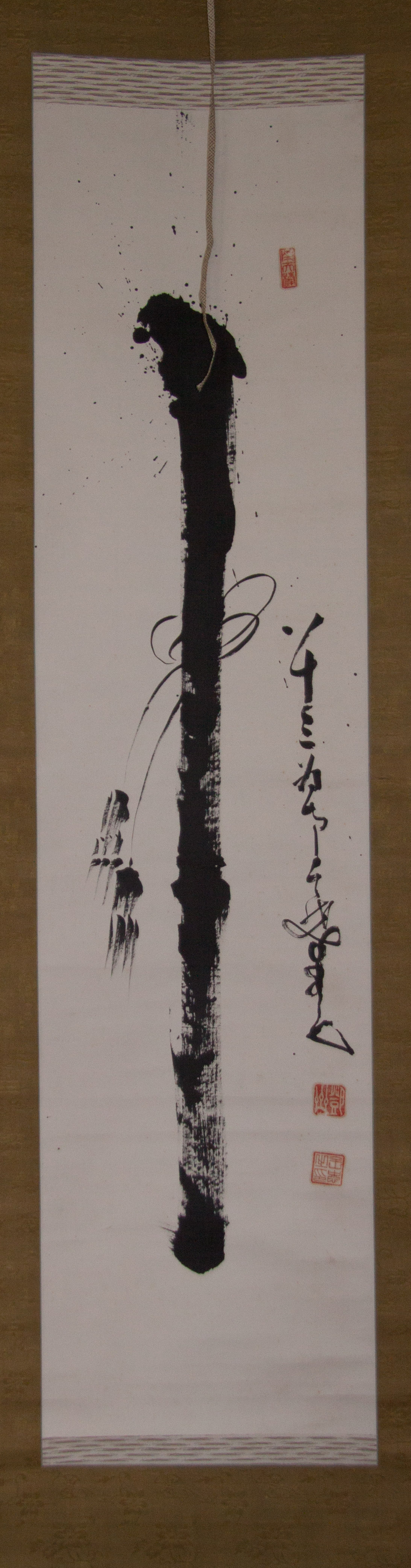

Photo:LH

I had another experience with a coyote — a real one! I was alone meditating in the winter in the hut behind the orchard. The snow was deep and I had snowshoed out to the hut. I entered, left the window shades down for extra warmth, lit a stick of incense, a candle, and took my seat. In the Zen meditation I practice, you don’t move during a sitting period. You don’t shift position, scratch an itch, or brush off a mosquito. You sit through it all, accepting everything with all the equanimity you can muster.

As I was sitting, I began to feel an eerie presence; someone was outside the hut. I decided to go against all of my Zen training and get up from my meditation cushion. I cautiously pulled up the shade. A great silver coyote stared into my eyes. She gazed and I gaped back unblinking for more than a minute. Then she turned and plunged into the deep snow, and I sat back down enlivened by the gift of her presence. The coyote must have been sleeping under the hut, which sits on pillars a foot off the ground, when she realized I was inside.

Tamarack Song, a tracker and guide who uses traditional hunter-gatherer skills he learned from elders and aboriginal people all over the world, writes of his early apprenticeship:

Irritated by my endless string of questions while I tagged after him [a Blackfoot Elder], he turned around and said, “Tamarack, when you talk, there’s no room for listening. When you ask a question, you are not really questioning, because you think you know what you need to learn. If you’d let yourself listen, you’d get answers to the questions you don’t know how to ask. Only when we listen do we learn . . .

The Blackfoot elder is instructing Tamarack to really listen to the person who is speaking to him; he is also telling Tamarack to trust his inner voice. My experience with the coyote in the snow affirmed that it was good to listen to my inner voice and not rigidly follow a set of rules. Of course, I wouldn’t stand up in the middle of the Meditation Hall with a hundred other meditators, but in my own hut, alone, I could, and I was grateful that I did.

Lately, I’ve been trying to listen to this inner voice — to really hear it, to be a better listener. It’s not easy. It’s hard to distinguish it from all the yips and yaps, my own desires and judgements. That’s why silence is so important. It’s only in silence that we hear. Mozart is supposed to have said, “The music is not in the notes, but in the silence in between.” The book I was reading yesterday attributed the same quotation to Debussy. I guess it doesn’t matter who said it. The gift of listening is that it takes us to a place we might not have gone on our own.

Inside the Wave, Sculpture:LH