On Christmas last year my stepfather gave me a gift, but before I started to open it, he said, “Wait. There’s baggage that comes with this gift, Linda.” I know about gifts—after all I am the daughter and step-daughter of anthropologists.

“All right,” I said, and started opening the wrapping paper.

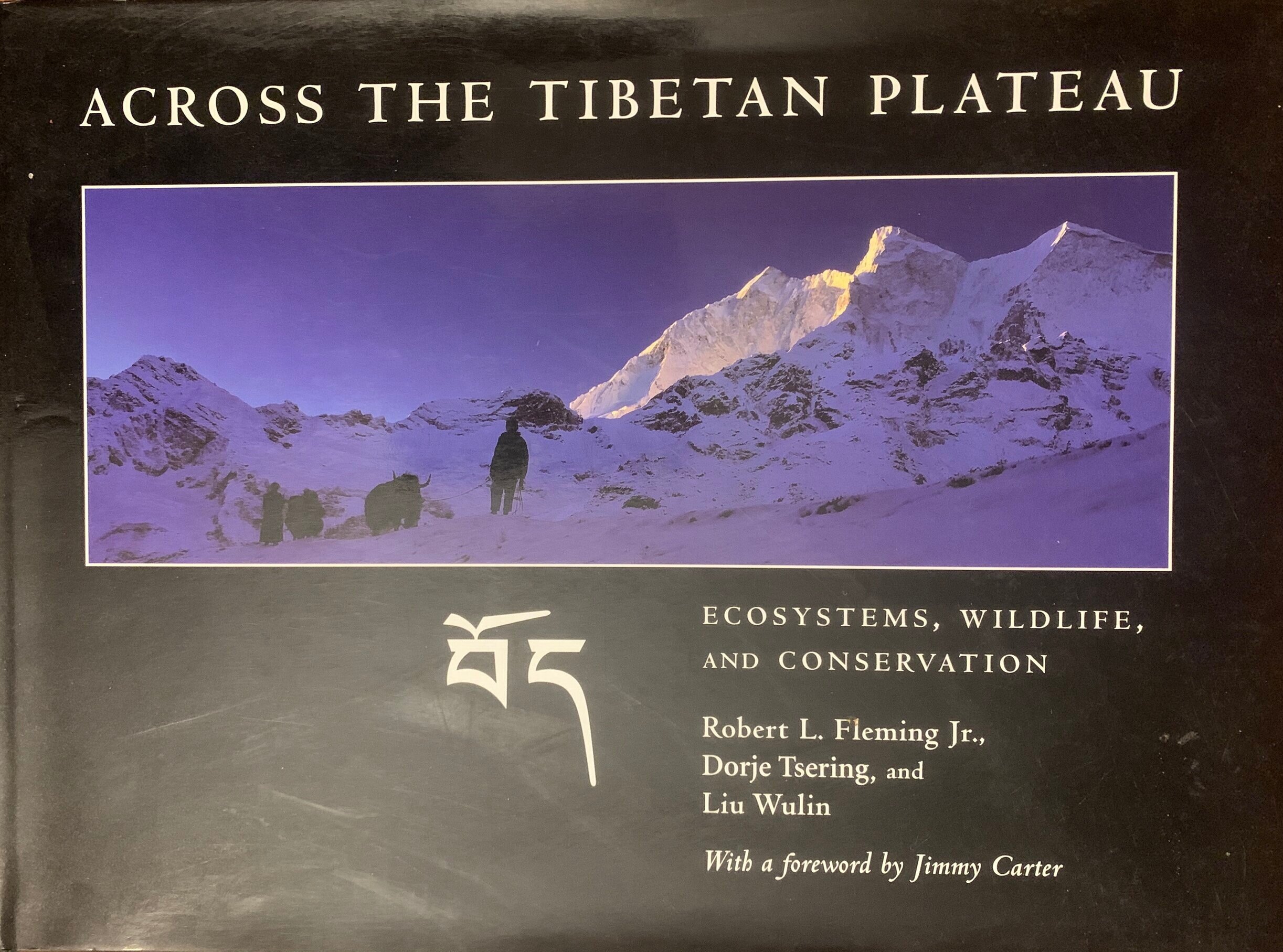

It was a coffee table book on Tibet, one that in all likelihood he had picked up from his living room side table. Bill has been fascinated with Tibet since a brief visit there five years ago.

“I want you and Blase to take me to Tibet,” he said.

I love this man. He married my mother when I was myself a young bride, and they had a glorious and passionate life until she died in 1997. Bill is now ninety-two—I would do anything for him. He is the one person I often speak to about my mother, a courageous woman who remains a constant inspiration to me. Bill always sends me a note on her birthday.

Bill wanted me to organize our trip, not travel with an organized tour like his previous visit. But Tibet is not easy to enter. You have to travel either from Kathmandu or China. Outsiders cannot visit Tibet as one would a western European country, France for example—climbing the Eiffel Tower, visiting Notre Dame, or taking the train to Versailles. Any person visiting Tibet needs not only a Chinese visa, but a Tibetan visa, and a guide to go anywhere outside of the capital, Lhasa. I made contact with a Tibetan guide service, determined that our trip would benefit the Tibetan people.

I asked my daughter, Ariel, if she wanted to join the three of us, and she jumped at the opportunity. We talked about what painting supplies we would take with us and began looking forward to painting together. Meanwhile, well-meaning friends warned me it would be dangerous to take Bill from sea-level to over 12,000 feet.” They had a point, but when I mentioned this to Bill, he waved it off. “I’ll take Diamox and be fine.”

Obtaining our Chinese visas was the first hurdle. For various bureaucratic reasons Bill’s application was rejected twice, while ours went through after some artful arranging. Several weeks passed and the timing was getting down to the wire. Without Bill’s Chinese visa, we couldn’t apply for the Tibetan visas, and if we didn’t do that shortly, it would be too late. I called Bill.

“Bill, what do you think?”

“Maybe I’m just not meant to go,” he said.

“Well, if you’re not going, we’re not going.”

“Oh, no!” he said. You must go! The three of you must go without me.”

Getting our visas was arduous, but the re-applications, hotel reservations, letters, documents, and day by day plans had worn me out. I’d spent so much time organizing this trip, arranging, choosing accommodations, and so forth, that I was ready to let it go. Bill was the impetus; without him I was no longer sure about going.

I called Ariel and told her it didn’t seem Bill would get his visa in time and we needed to decide if we would go without him. Blase was on the fence because his mother’s health was failing. I didn’t know what Blase would decide. I hoped he’d come with us, but wanted her to know it might be just the two of us.

“It’s fine just the two of us.” she said.

“We’ll have to be courageous,” I replied.

“We can do it.”

She wanted to go no matter what. It was decided. Ariel and I would go with or without the men.

Detail from Journey, Outdoor Installation by Tristan Govignon at Old frog Pond Farm & Studio. Photo: Robert Hesse

Blase visited his mother and after speaking with her and his brothers, he felt more at ease about being away and said he wanted to join us. On Monday, I wrote to Samdup, the person arranging our Tibetan itinerary, wired payment for the trip, and gave the ok to apply for our three Tibetan visas. These were being processed when on Thursday afternoon Bill received his Chinese visa from the embassy.

I wrote again to Samdup:

Bill has his visa. I have attached the copy below. Please add him to our trip.

I didn’t know if there was time to re-apply as a quartet, but I was determined to do everything possible to have Bill go with us. Samdup replied that they needed to resubmit everything, but he would see what he could do to expedite the process. We still have not heard definitively, and our flight to Beijing leaves on Thursday, but we are planning to board our China Air airplane, fly to Beijing, and hopefully to Lhasa.

I still wonder a little, especially in the middle of the night, if we are we supposed to go. But I trust that without knowing the reason, there is something important for us to experience. Ariel and I are excited to share this opportunity with Blase and Bill, to visit a country surviving despite the trauma of its recent history, a country rich in spiritual teachings, one that has already brought so much wisdom to the West.

Cover Drawing by Robert Spellman for The Wisdom of Tibetan Buddhism, edited by Reginald Ray, Shambhala Pocket Library.