Long I lived checked by the bars of a cage;

Now I have turned again to Nature and Freedom.

—T’ao Chi’en, tr. Arthur Waley

I think about the purpose of my sculpture while our president-elect considers appointments of men to positions of power — men who are openly anti-Semitic, anti-abortion, anti-gay, anti-anyone different from that face they see in the mirror.

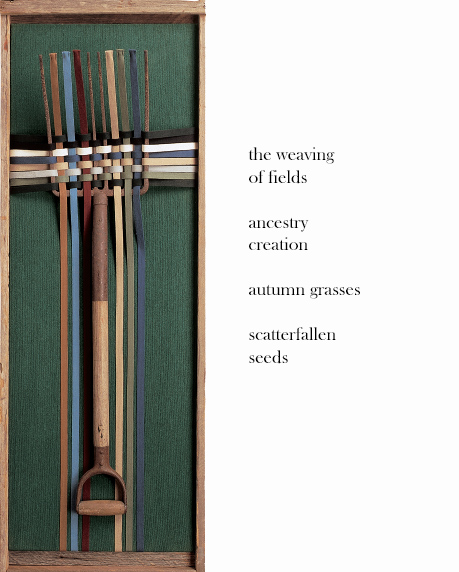

Birdcage, bronze figure, wood, and found objects, LH

When I am working in the studio, I have to separate myself from the frenzy of the world and quiet my mind. If I bring the chaos of the world into a sculpture I create more chaos. The process requires me to enter a sanctified space and focus on one thing. Post-election, I am finding this hard to do.

Two weeks ago, I submitted Birdcage along with several other sculptures for an exhibition on the theme, Home, Self, Spirit, Space. The prospectus asked for a statement about the work. Capturing what I do in a few sentences is always challenging, but I wrote, “I create small bronze figures and use either wood or found objects as ‘homes’ for these figures to inhabit. The natural materials and patina of age of the old objects give this work a context outside of the modern world. The sculpture creates a contained and lucid space the viewer can enter.”

In the Wave, bronze figure and wood, LH

Woman in Log, bronze figure and wood, LH

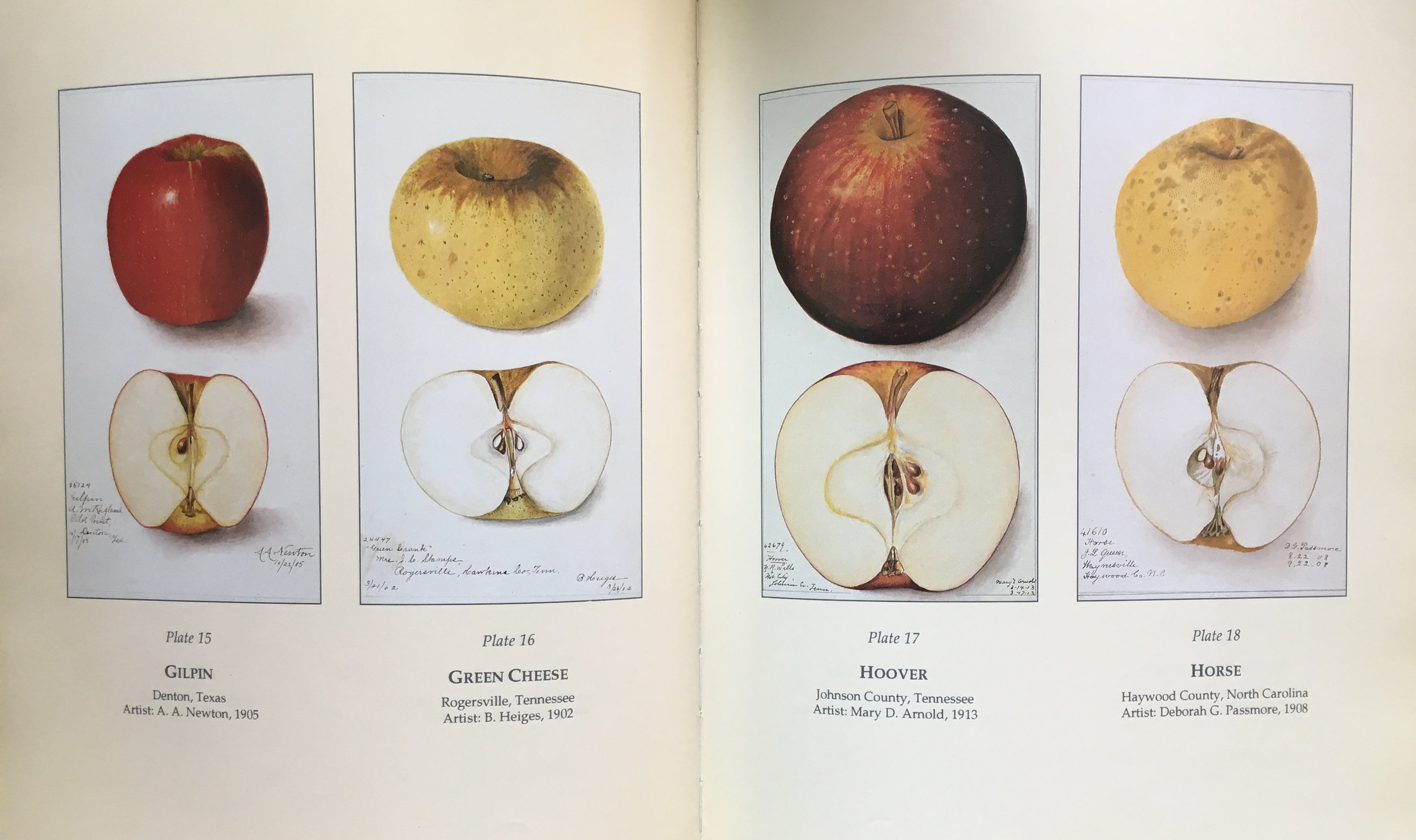

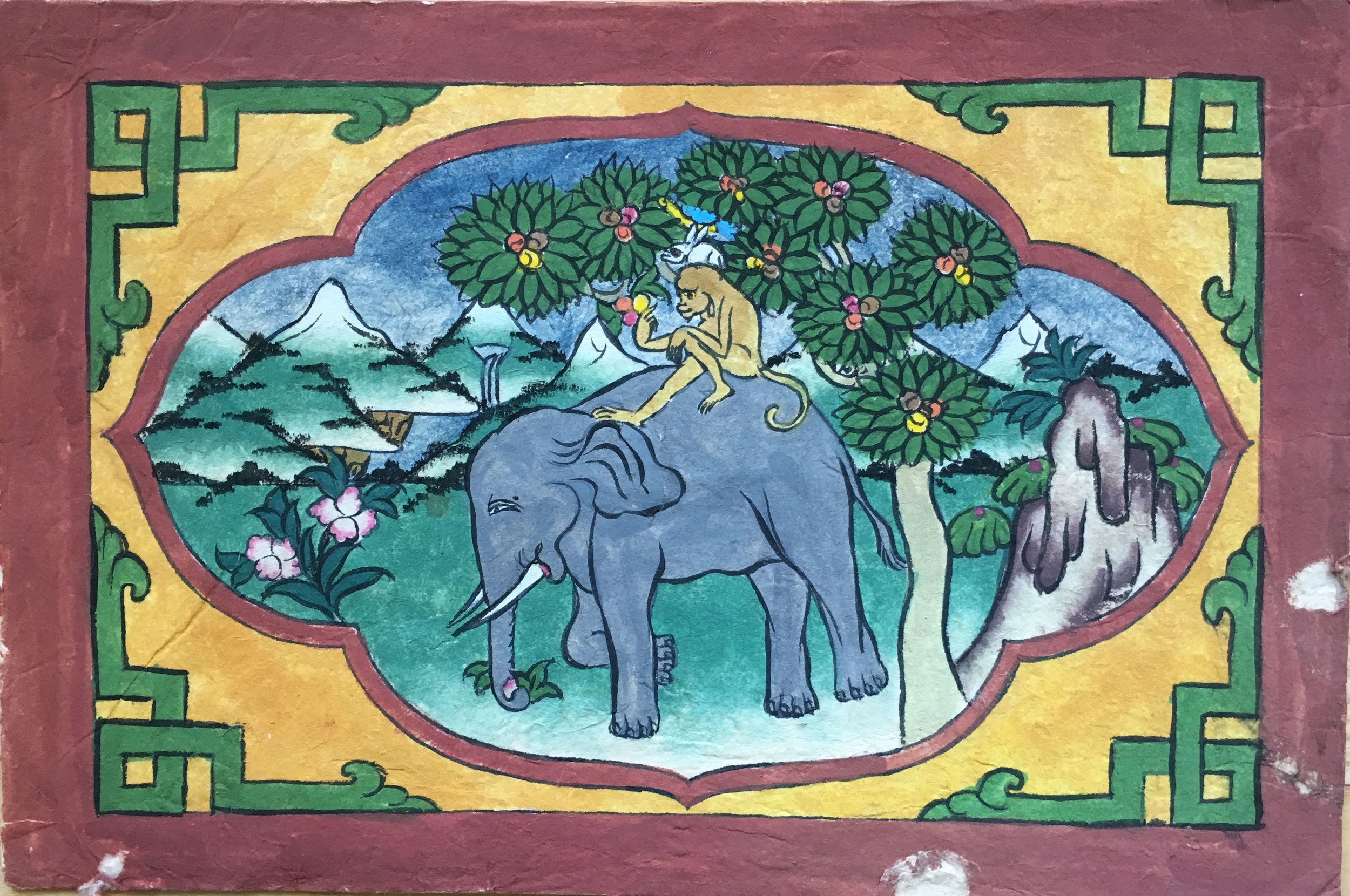

An orchard is also such a space. The wood nymph, Pomona, one of those lesser gods in the Roman pantheon, was the Goddess of orchards. She is often pictured with a curved pruning knife, walking among her trees, splitting the bark, and inserting grafts. She waters them from a nearby stream with the same attention one would give a new lover. Yesterday, my daughter Ariel and I walked through our orchard. We pruned out an armful of water sprouts, those twigs that grow several feet straight up in one year on apple trees. We’re working together on a sculpture for an exhibit using apple prunings as the primary medium. Ariel is grafting tree branches, covering the largest wall in the studio while I sculpt the small figures that will populate the tree. We work in silence, usually without stopping for lunch, only speaking when it is about the process.

Ariel Matisse grafting apple branches.

Some art is explicitly about fighting injustice and racism, it speaks loudly and will not be silenced. And it is important! But right now, I find it helpful to sit quietly, sculpt small figures and bend apple branches with my daughter. It feels good to work in the studio where we can recharge and aspire to make art that will breathe fresh air into the world.

P.S. Look closely at Birdcage, the door is open!