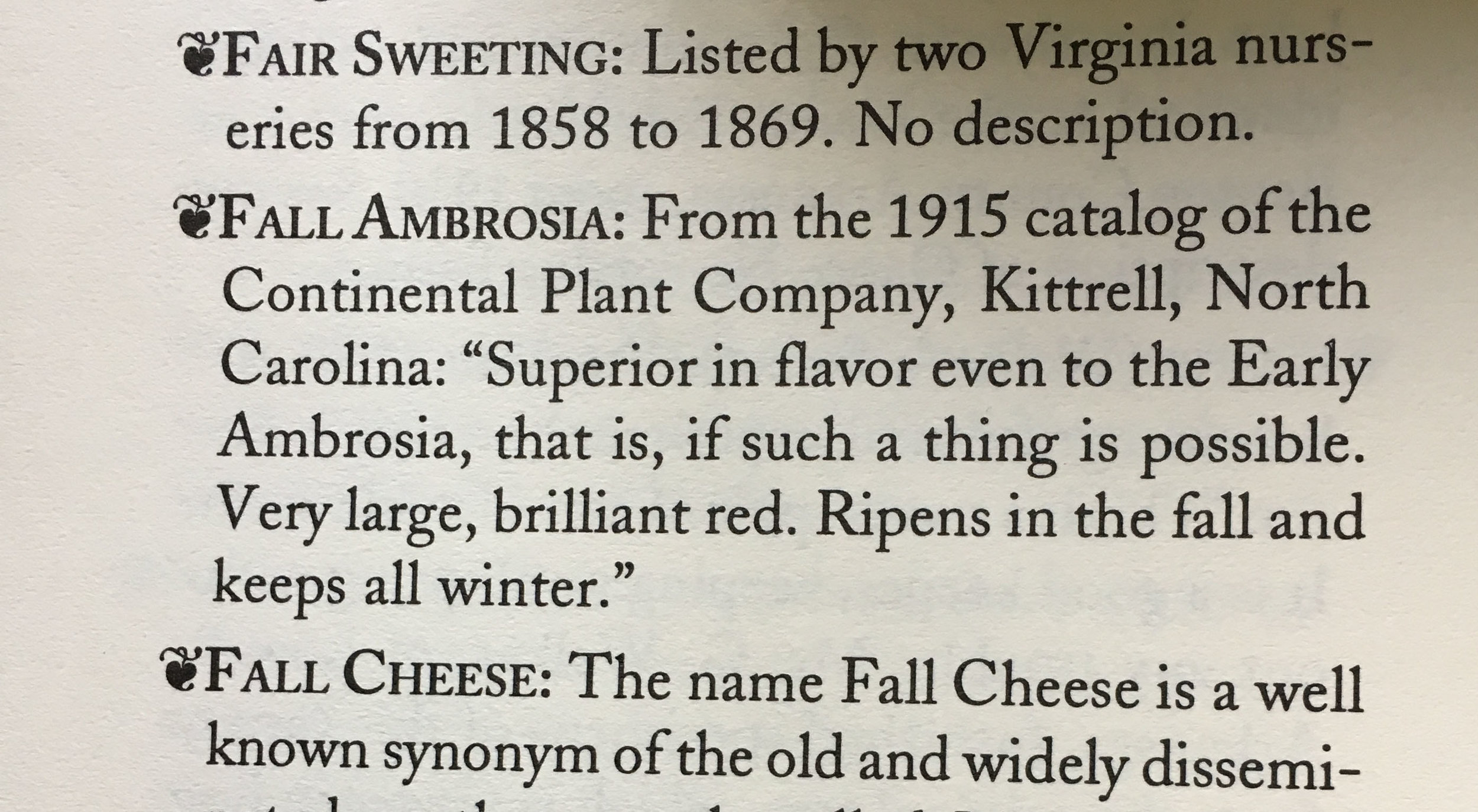

I celebrated my 60th birthday this week. My partner, Blase, gave me a first edition of the book Old Southern Apples, written by Lee Calhoun. Southern apples might sound like an oxymoron, since not many people think of the South as an Eden of apples. But over 1300 varieties originated south of the Mason-Dixon Line, and these apples are an important part of the area’s agrarian history. Old Southerners not only talk about Bloody Butcher corn and Red Ripper peas, but the now extinct apples like Fall Ambrosia (sounds so delicious), and the still available Limbertwigs.

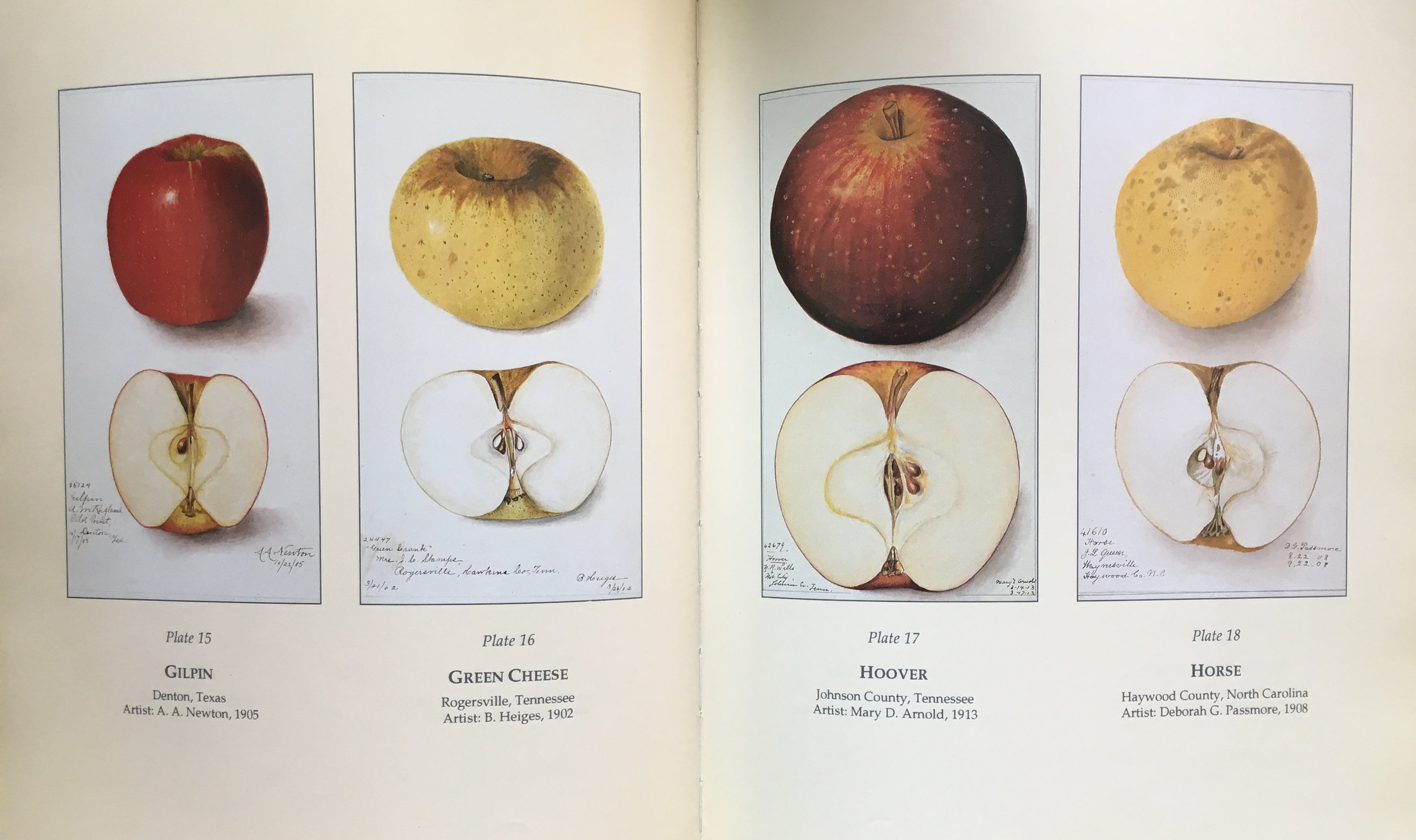

Old Southern Apples describes the unique features of over 1600 apple varieties (though 300 of them originated elsewhere but were grown in the South). The book divides these apples between 300 still growing or available at nurseries and 1300 now extinct Southern apples, the names and descriptions mostly taken from old nursery catalogues (a coincidence that both numbers are 300). The book also contains forty-eight plates of hand-painted apple pictures selected from the seven thousand in the collection of the National Agricultural Library. That was from the days when the United States Department of Agriculture hired artists!

Old Southern Apples, Plates 15 - 18; Photos: Jerry Markatos

As you may know, apples grown from seed are the unique progeny of two parents, because the blossoms are cross pollinated. Most of these seeded trees crop with hard, sour, or small fruit, better for the hogs than for eating off the tree. Some apples are good for making hard cider and apple cider vinegar, but a few trees out of a thousand planted might produce unexpected, remarkable apples that would be given names and propagated. Of the 1600 apple varieties mentioned in this book, all of them grew from seed to be extraordinary apples. In the South, whether the settlers were large landowners or tenant farmers, they all planted out their orchards with seeds, they didn’t set out grafted rootstocks. It was the way it was done.

Today, it would be the rare individual who would scatter seeds to plant an orchard. After all, who would want a collection of wild apples? Large orchardists order sapling trees from wholesale nurseries in the thousands or even ten thousand. Blocks of the same variety, interspersed with another variety for pollinating, are planted. It is the researchers who cross apples and come up with new varieties for orchards to trial. A few apples become the darlings of the marketplace. This approach to apple growing is very different from the grand creativity that nature realizes with such ease. As Lao Tzu said, Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.

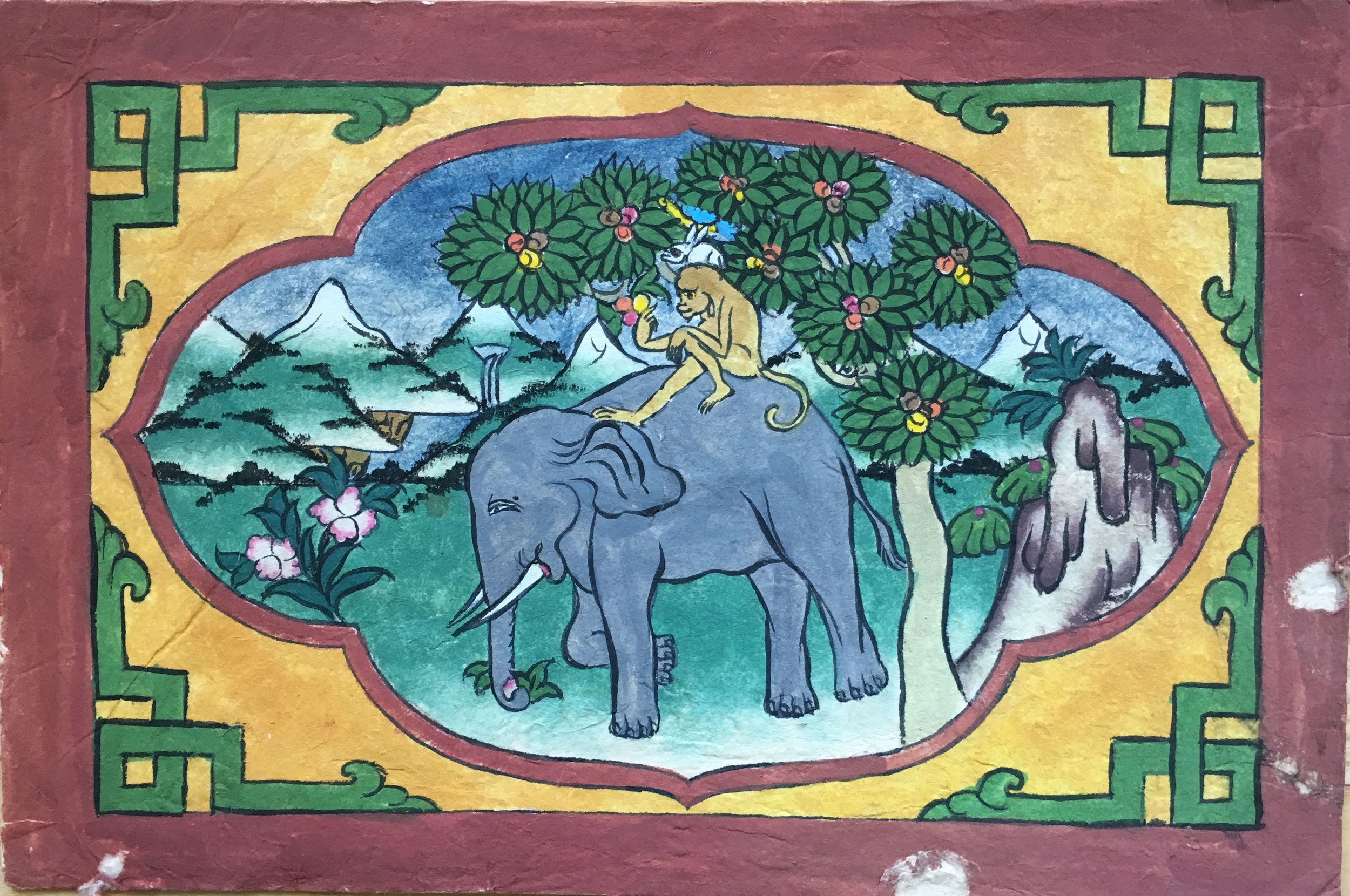

Inside my card, Blase tucked a print-out of a Buddhist tale. When King Mahajanaka, an earlier incarnation of the Buddha, was traveling through a park, he saw a monkey sitting on a branch of a mango tree. The King longed to stop and pick a few mangoes, but traveling with his large retinue, he had to continue without stopping. He decided he would sneak back alone that night to pick a few mangoes. That night, when he got to the grove, he lifted his torchlight and saw that someone had gotten there before him. The mango tree was stripped bare of fruit; its limbs were broken and its leaves lay scattered everywhere. He was saddened to think that this beautiful tree would likely not survive this ravagement. Then he saw another mango tree, one that had not been harmed. He realized that this tree avoided the carousing thieves because it had no fruit. The King returned and pondered his experience with the two mango trees. He decided he would renounce his title and give away everything he owned. He would become a tree without fruit. I love the story of the King Mahajanaka and the mango tree, but it could be taken as a teaching in renunciation. As many of you know, the orchard at Old Frog Pond Farm had no apples this year, and it was not because I renounced my title of orchardist.

The Birthday card Blase gave me was hand painted in Bhutan; he had saved it from our trip seven years ago. It is of a bird on a rabbit on a monkey’s shoulder, on an elephant (the bird and rabbit are hard to see). They are walking under a mango tree laden with fruit. It is an illustration of the “Four Harmonious Friends,” a much loved Bhutanese tale. These animals worked together; the bird planted the seed, the rabbit watered the sapling, the monkey fertilized it, and the elephant protected it until it grew into a beautiful tree with fruit for all of them.

"Four Harmonious Friends" handpainted in Bhutan

I loved my gift of so many fruit related stories. Our orchard is so much more than its acres of grafted trees. It’s a language we speak and share; a wild grove of poetry, paintings, sunsets, clouds, blossoms, and, hopefully next year, delicious fruit.