While I dream of wild apples and of someday visiting the forests near Almaty, Kazakhstan, the birthplace of our domestic apple, the commercial apple world is moving in the opposite direction. ‘Club’ apples represent its most recent advance. These apples are grown by a select group of exclusively licensed growers. The SweeTango is one of the first club apples. A few years ago, a limited number of orchardists bought shares to be part of the ‘club’ who can grow this apple. They call themselves The Next Big Thing cooperative.

I found this shocking and emailed my apple friend, Frank Carlson, one of the owners of Carlson Orchards in Harvard. He graciously said to come on over. Frank told me that he hadn’t bought into the SweetTango Club, but when he saw the next offer of a club apple, the Evercrisp, he joined. Last spring, they received their first shipment of Evercrisp trees, a cross between the ever-popular Honeycrisp and the Fuji apple. Carlson Orchards will be the only orchard in our area that has this apple, and they will pay a yearly fee determined by their harvest. It will be illegal for me to take a piece of scion wood from one of Frank’s trees and graft my own Evercrisp apple.

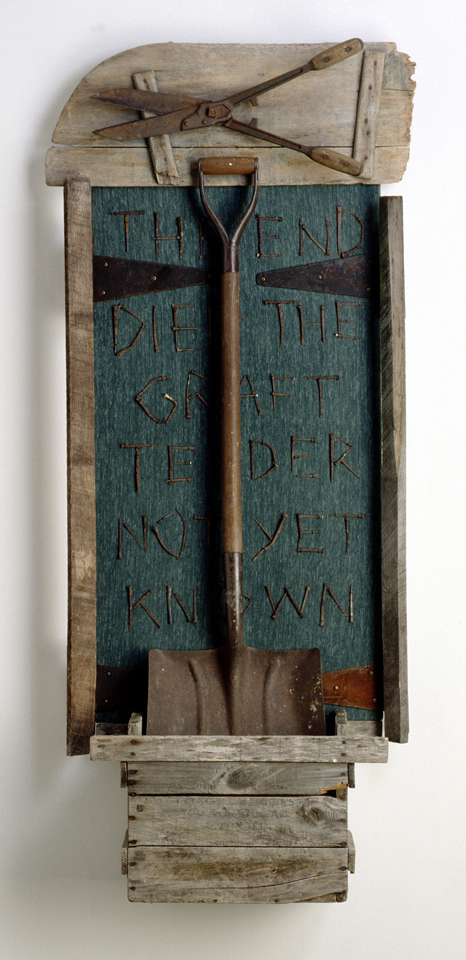

Grafting the 17th century French apple, Caville Blanc d'Hiver at Old Frog Pond Farm.

The trading of scion wood among apple aficionados is quite common. Earlier this year, I received an email from someone desperately seeking the Lyscom apple for his orchard of heirloom Massachusetts apples. When I responded that I had some to share, Russ Caney was so excited he drove up from the South Shore that afternoon. He said that he had contacted small nurseries all over the country. He brought me a few rare varieties, including Caney Fork Limbertwig, his namesake apple, which originates in the Caney Fork area of the Cumberland Mountains in Kentucky. This apple belongs to the Limbertwigs, trees that all have a weeping shape; I had never heard of these apples.

In Harvard, there is a small community of backyard apple growers loosely organized by Libby Levison. After our grafting workshop, she passed on some of the leftover scion wood to a mutual friend and apple grower, Brian Noble. He sent me this note in reply.

Linda,

Thanks so much for the scions you sent via Libby. That was very nice of you to share such unique stock. I thought I was being "authentic" with my Roxbury Russet. Now I'm in the big leagues. I had time to graft them today. I hope they take. I don't have the magic touch that Libby does.

Brian

I appreciate this apple camaraderie. However, the SweeTango, EverCrisp, and other club apples remain illegal to share. There is, of course, an economic reason behind the club phenomenon. There’s money that goes into the research and development of a new apple variety, and the developers want to profit. I certainly don’t understand the intricacies of apple economics, but I resent the restricted ownership of our food and plants. Theophrastus, a philosopher and student of Aristotle, wrote a treatise on propagation using scion wood ca. 300 BC. Sadly, the history of apples has now changed, and we can no longer freely exchange some new apple varieties.

On a more cheerful note . . . The apple scions I mentioned in last week’s post, The Graft, are putting out their first leaves!

And, now, Libby, Brian, and I all have Russ Caney Limbertwigs growing in Harvard. It is good to be part of this complex, conflicted, and passionate apple world.