At the farm, for the month of June, on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays, I will concentrate on the tasks in front of me. On the other days of the week, as much as possible, I plan to escape to a rental house on Cape Cod. It’s between Wellfleet and Truro on the ocean side, an area I love and where I have vacationed with my children since they were young. My plan is to work on a book I have been writing off and on for five years and more. I would like to finish it, am feeling the pressure to complete this project—or if it seems not-finish worthy, eject it. Send it over and out into the ethers—delete, delete. After all, it is only electronic bits of information.

But thankfully there is Annie Dillard. In her book, The Writing Life, she says, “Writing a book full-time takes between two and ten years.” She offers me relief. I have not been working full-time on this project. I have two other full-time jobs—art and the farm. She also says:

A work in progress quickly becomes feral. It reverts to a wild state overnight . . . As the work grows, it gets harder to control: it is a lion growing in strength. You must visit it every day and reassert your mastery over it. If you skip a day, you are, quite rightly, afraid to open the door to its room.

I understand this ferocity. At home, I cannot open the book for it might take over, grab hold of a leg and not let go. When I am on the road, or somewhere else, anywhere really, on a train, in a hotel room, and now at the Cape, for some reason the danger is not present and I can turn to it, dive in, and to my astonishment, do the work I love—the search to shape of an event, or an object, with words. And then there is the book itself, becoming an entity of its own, taking over, devising its own life. The two of us now living together.

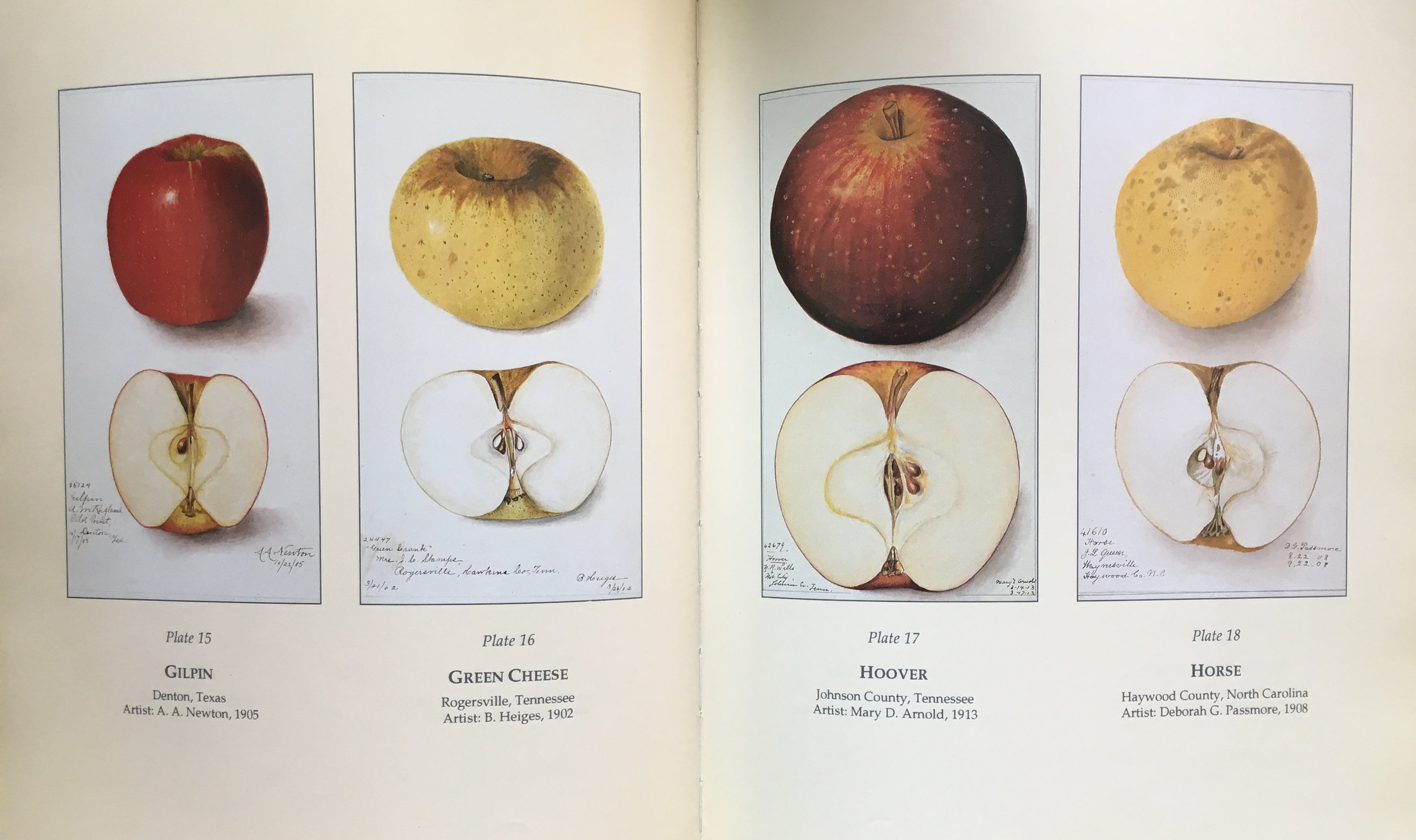

I am writing about moving to Old Frog Pond Farm, assuming the care of the abandoned orchard, and committing to bringing it back organically. What got me here? Why did my marriage fail? How has my Zen practice braided through the orchard work? And what lessons have I learned that appear in my art?

Annie Dillard again:

The strain, like Giacometti’s penciled search for precision and honesty, enlivens the work and impels it toward is truest end. A pile of decent work behind him, no matter how small, fuels the writer’s hope . . .”

Yes, she is right, I do have hope. And then I fall short, I fail as I judge what I am writing. I hear myself say, I am not a real writer. I read other writers whose work I admire and see how my writing lacks their skill. How does one learn to write? Annie Dillard, thankfully, answers this question.

The page, the page, that eternal blankness, the blankness of eternity which you cover slowly, affirming time’s scrawl as a right and your daring as necessity; the page, which you cover woodenly, ruining it, but asserting your freedom and power to act, acknowledging that you ruin everything you touch but touching it nevertheless, because acting is better than being here in mere opacity; the page, which you cover slowly with the crabbed thread of your gut; the page in the purity of possibilities; the page of your death, against which you pit such flawed excellences as you can muster with all your life’s strength; that page will teach you to write.

Other than write, I take beach walks. On my first one, I stopped when I found a horseshoe crab upside down, it’s little pinchers barely moving. I turned it right side up and watched as it began to move. Its long tail spine pointing to where it had come from, its hulk moving towards the waves. It stopped after about ten feet, and I had this sickening feeling that it was dying, right there, in front of me. I touched its pointer, wriggled it from left to right, and it started up again, slowly, another six feet, scraping its way over the sand, leaving its foot-wide trail. We went through this ritual several more times, my teasing the pointer, the crab starting reluctantly to move, but each time it seemed to be moving more slowly.

When it finally reached the waves, I felt this was its most precarious place to be. It stalled. It waited. The surf poured over its hard shell. It seemed to be waiting for something. Then a large wave carried it into the jumble of surf. I saw was the tail spine, sticking up above the wave, pointing.